Deep into Mystery Games - A Design Analysis

Return of the Obra Dinn - One of the most successful Fill-it-Out Mystery games

Return of the Obra Dinn - One of the most successful Fill-it-Out Mystery games

How Does a “Fill-it-Out” Mystery Game Work?

When people talk about mystery games, they often jump straight to the vibe: dusty libraries, foggy streets, cozy parlors with tea, or shadowy crime scenes. But if you look past the atmosphere, you’ll notice that most detective-style games on PC share a core set of mechanics.

I like to call this type of game a Fill-it-Out Mystery. You start with a little skeleton of knowledge, and then slowly fill in the blanks until the bigger picture emerges. Whether you’re solving murders on a doomed ship (Return of the Obra Dinn), piecing together a cursed golden idol, or identifying flowers in a cozy plant shop, the bones of the gameplay are surprisingly similar.

The Core Ingredients of a Fill-it-Out Mystery

All of these mechanics are used across mystery games. However, any can be skipped. In my experience, it ALWAYS leads to a worse game. The most beloved games in the genre has all of them, or skip maximum one or two.

WARNING: THIS ARTICLE CONTAINS SCREENSHOTS WHICH MAY SPOIL SOME OF THE GAMES DISCUSSED. DO NOT THINK TOO HARD ON THE IMAGES.

Here are the mechanics that almost every Fill-it-Out Mystery game in this genre leans on:

Base Framework

The “anchor” that gets you started. It must contain some foundational knowledge of facts. Maybe it’s a family tree, a set of character portraits, or even just one artifact that sets the scene. Without this, players feel lost right from the beginning. In Roottrees, it is the family tree structure and relationships. In Obra Dinn it is a death and their portrait. In Golden Idol it is the literal slots on the scrolls, which is color coded to what should go in there (as well as sentence structure)

In Roottrees Are Dead, the player always knows how the family tree looks

In Roottrees Are Dead, the player always knows how the family tree looks

Artifacts

Your information bank. These could be 3D scenes to wander through, documents, letters, or even plants. You can check and re-check them forever, and they’re where most clues live.

In Strange Antiquities, the player has 50+ items to investigate using different tools and senses.

In Strange Antiquities, the player has 50+ items to investigate using different tools and senses.

Reference Artifacts

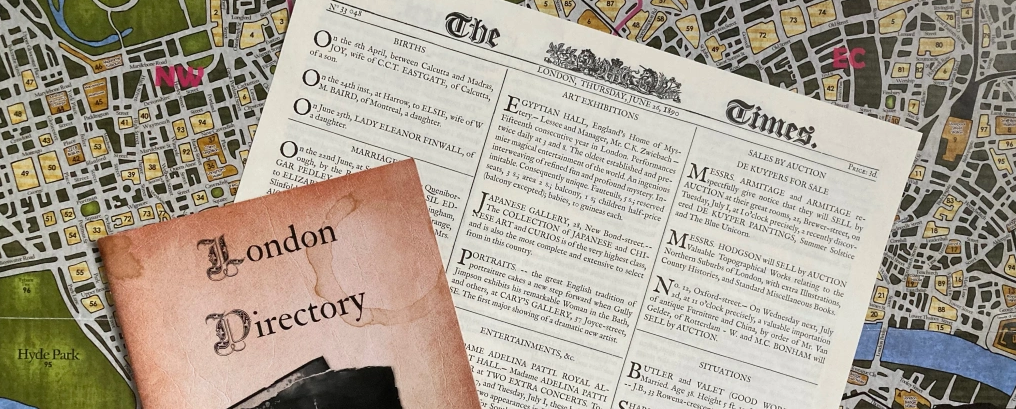

A special type of artifact, present in almost every mystery game. It contains a huge amount of information, to the point where it is not readable or useful for the player. However, if you know what you’re looking for, it is a goldmine to sift through. Examples are big maps, big newspapers, full multi-page books, search engines, and in some cases (Obra Dinn, Golden Idol), entire scenes.

In the boardgame Sherlock Holmes, Consulting Detective, there are many overwhelming reference artifacts for players to sift through, searching for people and addresses.

In the boardgame Sherlock Holmes, Consulting Detective, there are many overwhelming reference artifacts for players to sift through, searching for people and addresses.

Discovery

How you grow your bank of artifacts. Some games gate progress behind solving puzzles (Obra Dinn, Golden Idol), while others give you locations to visit or keywords to chase (Roottrees, Sherlock). There must be some way to gain new information.

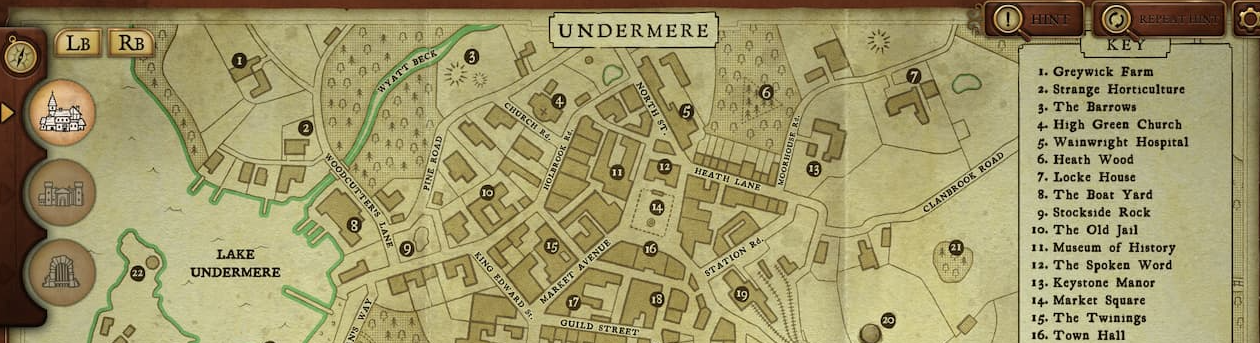

In the Strange games, the player gain new artifacts by exploring a map

In the Strange games, the player gain new artifacts by exploring a map

Truths & Clues

The actual facts you’re trying to nail down. Who died where? Which plant is which? How are these people related? These are the “answers” you’ll eventually plug into the framework. “Clues” is what I call partial facts; they aren’t plug-innable on their own, but can be combined with other clues to form a truth. Clues is a type of soft progress.

Clues in Obra Dinn comes in the form of small details you note in the scenes

Clues in Obra Dinn comes in the form of small details you note in the scenes

Soft Progress

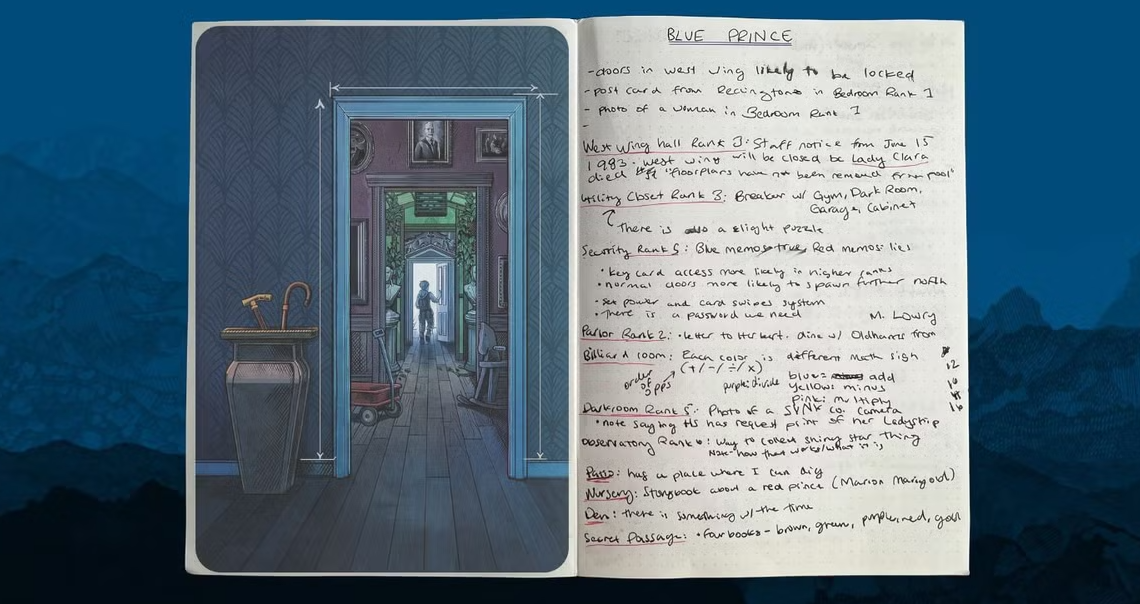

A way to keep moving forward even when the hard puzzles stump you. Examples. This one can be skipped freely, but the game becomes a lot worse. It just feels worse for the player. Combining clues using mechanics feels so much better than just doing so in the players head. Blue Prince solves this by simply telling the player they’re expected to have a physical notebook. Obra Dinn lets the player slot in “Unknown Officer” to indicate something they know. Strange Horticulture/Antiquities let you tag objects even when you don’t know what is is. Golden Idol has NO soft progress, but survives by having bite-sized self-contained chapters, and confirming hard progress liberally. Speaking of…

In the 3rd room you ever find in Blue Prince, the game tells you to get a physical notebook. They also include one in the limited physical edition of the game!

In the 3rd room you ever find in Blue Prince, the game tells you to get a physical notebook. They also include one in the limited physical edition of the game!

Hard Progress

The game’s way of confirming you’re right. Obra Dinn locks in every three correct identifications. Golden Idol confirms a whole chapter at once. Without this, mysteries feel endless and exhausting. At some point, the player must know if their hypothesises are true.

- Obra Dinn: After 3 correct guesses, guesses locks in.

- Golden idol: After a full section is completed, they lock in.

- Roottrees: After 3 correct guesses, guesses locks in.

- Sherlock, Consulting Detective: None, which sucks (due to being a TTRPG). It is the largest flaw of the game.

- Strange Horticulture: When someone gives you a task, you get hard confirmation if they accept the plant.

- Strange Antiquities: Same as Horticulture, but fewer plants.

In Golden Idol, the game tells you if you complete a scroll correctly, and gives you a heads up when only one or two is incorrect.

In Golden Idol, the game tells you if you complete a scroll correctly, and gives you a heads up when only one or two is incorrect.

Without hard progress, it isn’t a game.

Meta Indicators

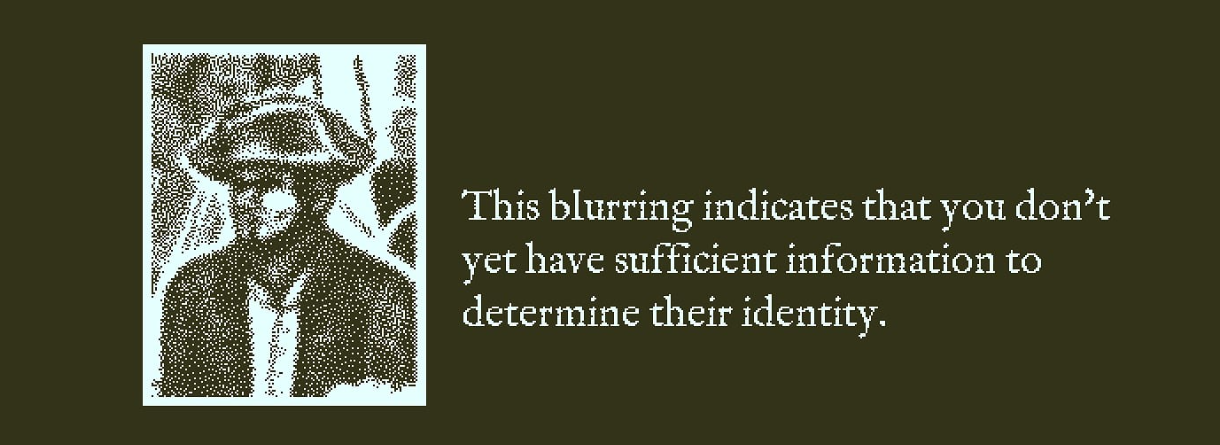

Little nudges that stop you from flailing around. Difficulty ratings, hints, or blurred-out options remind you what’s currently solvable and what isn’t. It is critical for the player to not feel like their effort is wasted. The creepy voice in the back of the players head saying “The mystery you’re spending hours trying to solve? You don’t have the information necessary”. We must indicate to the player what they should spend their time on.

- Obra Dinn: Difficulty marks on people (1 is easy, 2 is harder, 3 requires leaps of logic). Also, blurred photos (Base knowledge) for characters you currently don’t have enough info to guess.

- Golden idol: Hints when you have 1-2 errors in a scroll. (”1 or 2 incorrect”). Also self-contained scenes + guesses gives a cutoff of relevant information. Also has a clue system to deal with frustration.

- Roottrees: Stars in the beginning to give clues where you should begin. Also has a clue system to deal with frustration.

- Sherlock, Consulting Detective: None, except a single clue you can fetch.

- Horticulture: Gives you clear tasks 1-by-1 which is implied you can solve.

Expectations and trust is everything. The player must trust that you won’t screw them over. Meta indicators helps you avoid it.

Obra Dinn would be nearly unplayable unless the game told you which characters are solvable with your current information.

Obra Dinn would be nearly unplayable unless the game told you which characters are solvable with your current information.

Atmosphere

The glue that holds it all together. The feel. The mechanics might be similar, but the feel is what sets games apart: Obra Dinn’s bleak insurence-agent tragedy vs. Strange Horticulture’s cozy tea-time puzzle-solving.

Examples:

- Obra Dinn: Insurance investigator. But the real atmosphere narrative is the life of the sailors, because you’re literally in the middle of the story taking its place.

- Golden idol: Similar to Obra Dinn but less immersive. In the 2nd game, the meta layer gives more of an investigator feeling.

- Roottrees: The 3D room and intro gives the feeling of a semi-cosy investigator searching the internet.

- Sherlock: Very little atmosphere from the game. However, physical artifacts and being a table top game allows you to create a peak atmosphere. The game should push for it harder.

- Horticulture: Peak meta atmosphere. Cosy make-some-tea work, by having a first-person narrative where people come talk to you, asking you thinks, and making requests. You run a business day by day.

Jupiter, Destroyer of Worlds. Always pet the cat.

Jupiter, Destroyer of Worlds. Always pet the cat.

Where Games Trip Up

If a game misses one of these pillars, players notice:

- No base knowledge? You’re lost before you begin.

- No discovery? Everything is dumped on you at once, which kills pacing.

- No soft progress? You’re stuck staring at the same difficult riddle forever.

- No hard progress? Breaks the game unless it is less than 1-2 hours long.

- No meta indicators? You waste time trying to solve things that aren’t solvable yet.

- No atmosphere? Even if the mechanics are solid, the game just feels bland.

It’s a delicate balance: a little too loose and players feel adrift, a little too rigid and they feel railroaded.

The Case of the Golden Idol - Another excellent example of the genre

The Case of the Golden Idol - Another excellent example of the genre

Why This Matters

Once you learn to spot these mechanics, you can evaluate mystery games without even touching the theme. Whether it’s Victorian detectives, cursed idols, or cozy plant shops, the Fill-it-Out Mystery genre is really about how games structure knowledge, discovery, and confirmation.

So next time you’re browsing Steam and see a “detective” or “investigation” tag, ask yourself:

- What’s the base knowledge?

- How do I discover new clues?

- How does the game confirm I’m right?

- And does the atmosphere match the detective fantasy it’s selling?

Answer those, and you’ll know exactly what kind of mystery experience you’re in for. As a game designer.

As a player, forget all of this and enjoy the journey. I freaking love mystery games.